Name of Monument:

Benedictine Abbey of St. Theodor and St. Alexander

Also known as:

Monastery Ottobeuren

Location:

Ottobeuren, Bavarian Swabia, Germany

Benediktinerabtei Ottobeuren

Sebastian-Kneipp-Str. 1

87724 Ottobeuren

T : +49 (0)83 32 79 80

F : +49 (0)83 32 79 81 25

E : bildungshaus@abtei-ottobeuren.de/webmaster@abtei-ottobeuren.de

Date:

1711–1731: monastery building; 1717–1724: economy building; 1737–1766: church; 1739–1740: government building

Artists:

Monastery complex (selection), architecture: Father Christoph Vogt OSB (1648–1725), Simpert Kramer (1675–1753), Andrea Maini (b. 1683); stucco, among others: Johann Baptist Zimmermann (1680–1758), Andrea Maini (b. 1683), Cristoforo Volpini (d. 1733); frescos in the Imperial Hall, its forecourt and south stairwell: Karl Jakob Stauder (1694–1751/56); frescoes of the Theatre Hall and north stairwell of the Imperial Hall: Franz Josef Spiegler (1691–1757); ceiling paintings of the Benedictus Chapel, the Winter Abbey and the Prince’s Rooms: Jacopo Amigoni (1682–1752)Abbey church (selection), architecture: Simpert Kramer (1675–1753), Johann Michael Fischer (1692–1766); frescoes: Johann Jakob (1708–1783), Franz Anton Zeiller (1716–83/94); stucco and altar architecture: Johann Michael Feichtmayr (1696–1772); sculpture and design of the choir stalls: Johann Joseph Christian (1706–1777); joinery of choir stalls and confessionals: Martin Hörmann (1688–1782)

Denomination / Type of monument:

Ecclesiastical architecture (monastery, church and residence)

Patron(s):

Abbots Rupert II Ness (gov. 1710–1740), Anselm Erb (gov. 1740–1767)

History:

Founded in 764 by a count of the name Silach an important historical turning point for the Lower Swabian Benedictine Monastery Ottobeuren was the appointment to a sovereign Imperial Abbey in the 13th century. The land over which this rule extended included a multitude of villages, which later would be the financial basis for the economic and cultural expansion that the monastery experienced during the first half of the 18th century under the active Abbot Rupert Ness. Addressed as the “Hereditary Imperial Chaplain”, Abbot Rupert attempted to express his political closeness to the imperial court in Vienna with an enormous residence-like monastery. This expensive complex, on which a legion of local and trans-local artists worked, was such a strain on the finances of the abbey that the church building had to be delayed. Shortly before his death, Abbot Rupert commissioned the Swabian master builder Simpert Kramer for the construction of the church; however, in 1743, his successor transferred this responsibility to the famous architect Johann Michael Fischer from Munich, who was able to complete the prestigious building in 1766.

Description:

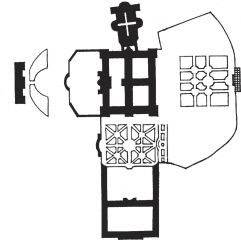

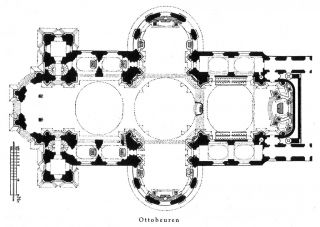

The monastery complex designed by Father Christoph Vogt is not built facing east as is common, but rather, appears as a rectangle stretched from south to north and is divided in the same direction by a middle axis. In this way the combination of a Benedictine abbey cloister and a sovereign imperial foundation is given a special architectonic expression. The duality shown with the eastern half as a monastery divided by the library wing into two equal courtyards, and the western half surrounding a single courtyard with an outward projecting main facade as a secular, princely residence building, simultaneously appears included and preserved due to the framing effect of the quadrant construction. The abbey church stands alone in front of the north wing and the choir connects to the monastery complex. Its facade with pompous columns and high towers is intended to be viewed from afar. Inside, the colossal columns and pillars intensify the perspective view, the focus of which is the high altar.

View Short DescriptionThe Benedictine Abbey Ottobeuren, dominated by its massive Late Baroque church with delicate Rococo interior, belongs to the largest and most marvellous Baroque monastery complex of southern Germany. The former imperial abbey, often called the “Swabian Escorial”, has always been a centre of science and culture culminating in its representative Imperial Hall, which lives up to expectations, with an amazing display of splendour.

How Monument was dated:

Archival documents, among which the diary of the 52nd abbot of Ottobeuren, Rupert Ness.

Special features

Cupola painting of the crossing

Crossing vault of the abbey church

c. 1757/60

Johann Jakob (1708–1783), Franz Anton Zeiller (1716–83/94)

The large, circular dome fresco is surrounded by four stucco cartouches with pictures of the evangelists that show the wonder of Whitsun and its meaning for the worldwide mission of the church. The architectural scenery of the step-platforms, balustrades and surrounding obelisks is typical of the art of mise en scène used for composing ceiling paintings.

High altar

Choir of the abbey church

1761–1763

Johann Michael Feichtmayr (1696–1772); Johann Joseph Christian (1706–1777); Johann Jakob Zeiller (1708–1783)

The bundle of columns of the powerful main altar made of stucco marble forms an imposing frame for the topics of the altarpiece, namely the Trinity and Redemption. To the sides, larger-than-life stucco figures of the apostles Peter and Paul in ecstatically-moved depictions admonish the faithful, while respectively, the painting reflects on the secret of faith. On either side are the figures of the holy bishops Ulrich and Conrad, both of whom were patrons of the Swabian bishoprics of Augsburg and Konstanz.

The Baptism of Christ

Northeast crossing pillar of the abbey church, above the baptismal font

1763/64

Johann Michael Feichtmayr (1696–1772); Johann Joseph Christian (1706–1777)

The Baptism group, conceived as a counterpart to the pulpit, belongs among the major works of Swabian Rococo for, among other reasons, the sensitive gestures of the sculptures and the capricious form of the altar-like framing.

Imperial Hall

Central projection of the west wing (3rd floor), Benedictine Abbey of St. Theodor and Alexander

1721–1727

Andrea Maini (b. 1683); Jakob Karl Stauder (1694–1751/56); Franz Anton Sturm (1690–1757)

The architectonic and artificial painting arrangement of the ceremonial hall celebrates the idea and dignity of the Holy Roman Empire as well as the fidelity to the empire and the potential sovereignty of the abbey. The ceiling fresco shows the Coronation of Emperor Charlemagne in 800; four pictures to the sides describe the empire's functions in relation to its services for the church: Ecclesiae propagatori (propagator of the Church), Ecclesiae propugnatori (defender of the Church), Hostium debellatori (combatant against enemies) and Scientiae fautori (patron of science). Larger-than-life statues of the last 16 emperors, placed in front of the pompous columns of the wall decoration, show respectful reverence to the ruling House of Habsburg.

Selected bibliography:

Jahn, P. H., “Wenigst habe in Wien und Rom davon alle Ehr. Die 'kaiserliche' Phase in der Baupolitik des Reichsstiftes Ottobeuren”, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 67: 2, 2004, pp. 183–200.

Hofer, S., Studien zur Stuckausstattung im frühen 18. Jahrhundert. Modi und ihre Funktion in der Herrschaftsarchitektur am Beispiel Ottobeuren (Kunstwissenschaftliche Studien 56), Munich/Berlin 1987.

Schnell, H., Ottobeuren. Kloster und Kirche (Große Kunstführer 2, 7th revised and enlarged edition), Regensburg 1979.

Wagner, H., Barocke Festsäle in bayerischen Klöstern und Schlössern, Munich 1974, pp. 112–6.

Hitchcock, H.-R., Rococo Architecture in Southern Germany, London/New York 1968, pp. 198–201.

Citation of this web page:

Maximilian Aracena, Peter Heinrich Jahn "Benedictine Abbey of St. Theodor and St. Alexander" in "Discover Baroque Art", Museum With No Frontiers, 2025.

https://baroqueart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;BAR;de;Mon12;35;en

MWNF Working Number: DE3 35

Back

Back

Add to My Collection

Add to My Collection