|

At no other time in history has the issue of art become vital to the Catholic Church as in the period following the proclamation of the theses of the Reformation by Martin Luther posted on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg (1517). Lutheran ideas spread rapidly through the printing and distribution of the famous German translation of the New Testament, until publication of a complete edition of the Bible in 1534.

The Reformation rejected the use of sacred images – considered pagan and idolatrous – and the wealth of sacred buildings, generally affirming the personal relationship between the believer and God, thereby abolishing any mediation of the Church. The impact on the reality of the time was unprecedented.

The Church of Rome saw its universal role, its very foundations, and the value of liturgical celebrations undermined. A review of the principles of doctrine, already anticipated by the feelings generated by confrontation with the Protestant movements, became urgent. It was at this stage that some religious orders, such as the Theatines (1524), Capuchins (1529) and Jesuits (1540), were established.

From the mid-16th century, the Counter-Reformation took up increasingly radical and uncompromising positions, and dialogue with the Reformation was drastically cut.

The Council of Trent (1545–63), while prohibiting idolatry, reiterated the importance of images as fundamental for the liturgy. The treatise on images by Gabriele Paleotti (1582) outlines the major renewal undertaken. The search for the simplicity of the early Church, the cult of the martyrs, and devotional paths were promoted as a sign of continuity between the Church of the time and the Church of the origins. It is from this time that an art of the Counter-Reformation can effectively be identified.

The aesthetic dictates of the Counter-Reformation evolved gradually with the emergence of Baroque art. Under Pope Borghese (1605–21) and especially from the papacy of Pope Barberini (1623–44) the use of images as a tool of persuasion became increasingly important. The Baroque gave an international dimension to the themes of the Counter-Reformation actually used by the ruling dynasties for political purposes.

The full reaffirmation of Catholicism, implemented from the late 16th century, spread throughout the Habsburg Empire after the Thirty Years’ War and especially in Moravia after the Battle of White Mountain (1620). In Hungary however, a Protestant presence remained, particularly to the east, and the Ottoman Empire was only defeated at the end of the 17th century.

The work of religious orders outside Europe was key to implementing the spirit of the Counter-Reformation.

Baroque became the universal language used by absolute monarchs to assert their power and legitimacy stemming form the authority of the Church.

|

Holy Family with Saints John and Elizabeth

Holy Family with Saints John and Elizabeth1588/90 Borghese Gallery Rome, Latium, Italy

Parish and Pilgrimage Church of the Assumption

Parish and Pilgrimage Church of the Assumptionc. 1710–1730 (Baroque redesign) Kaltenbrunn im Kaunertal, Tyrol, Austria

St. Vitus Cathedral, Rijeka

St. Vitus Cathedral, Rijeka1638–1659; 1725 Rijeka, Kvarner, Croatia

St. Florian with a View of Jihlava

St. Florian with a View of Jihlava1725 Moravian Gallery, Brno Governor’s Palace, Brno, Moravia, Czech Republic

A Member of Nagyszeben (Sibiu) Town Council

A Member of Nagyszeben (Sibiu) Town CouncilEnd of the 17th century Hungarian National Gallery Budapest, Közép-Magyarország / Central Hungary, Hungary

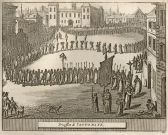

Procession and Auto de Fé

Procession and Auto de Féc. 1741 National Library of Portugal Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

|